Analysis: Think about the idea that investors can make the largest contribution to mitigating climate change by owning, and therefore encouraging, high emitters to decarbonise.

The core concept of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) has existed for centuries, dating back to religious codes banning investments in slave labour, through to divestments from South Africa to protest the country's system of apartheid. Over the last decade ESG considerations have become an integral part of most fund managers’ investment processes.

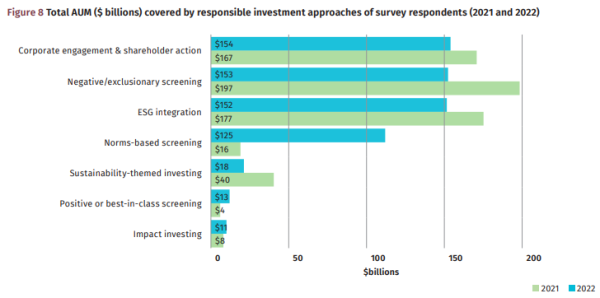

There are a number of approaches to implementing an ESG strategy within a portfolio. According to data published by the Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA) ESG integration, corporate engagement, and negative screening (exclusions) are the three most popular approaches to responsible investing and their wide-spread adoption continues to grow.

Graph: RIAA Benchmark Report NZ 2023

Negative screening is one of the oldest strategies in responsible investing implementation. This is the process of excluding specific companies or sectors from a fund of portfolio. This is achieved by determining the criteria for exclusion upfront based on a specific goal or goals. For instance, if the goal is to immediately decrease climate change’s impact, you may choose to exclude all fossil fuel companies from your portfolio.

Like the majority of investment managers, Octagon’s Responsible Investment policy includes negative screening of investment products with controversial weapons (including the manufacture or sale of assault weapons to civilians), the production of tobacco products, and the capture and processing of whale meat. Where we directly make the investment decision and the screening process identifies that the company derives five percent or more of its revenues from one of the listed activities above, then we choose not to invest. For a portion of our international equities and fixed interest investments where we invest in a third-party fund that we don’t directly manage, we take a different approach, choosing to publish regularly on our website any securities in the external manager’s fund that appear on our exclusions list. At appointment of the third party manager we carefully consider their approach to ESG to ensure it is comparable to ours and monitor this over the life of the relationship.

The trick with exclusions is understanding what is ‘in’ and what is ‘out’. And sometimes those distinctions and where to draw the line are not always clear for an investment manager or their clients. Octagon does not currently exclude fossil fuel companies as we believe investments in the best of these companies, those that have a credible, robust decarbonisation plan, can have a positive impact on global emissions reductions.

The production and use of fossil fuel is currently legal and considered essential in most modern societies. However, that doesn’t mean it will always be this way. To limit global warming to no more than a 1.5°C increase – as called for in the Paris Agreement – emissions need to be reduced by 45% by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050. Put simply, net-zero means cutting carbon emissions to a small amount of residual emissions that can be absorbed and durably stored by nature and other carbon dioxide removal measures, leaving zero in the atmosphere.

One local New Zealand company we look at closely is Genesis Energy (Genesis) which some investment managers exclude from their investible universe. Genesis is an integrated electricity generator and the second largest electricity retailer in New Zealand. The company owns a fleet of thermal and hydro power stations. Genesis also owns a 46% stake in the Kupe Joint Venture, which owns the Kupe oil and gas field that lies in the offshore Taranaki Basin.

Image: Coal Power Station, Huntly, New Zealand.

For the last financial year (FY24) Genesis’s total Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions were 3.2m tonnes, a 28% reduction from FY20. The bulk of these emissions come from the Kupe oil and gas field and burning gas and coal at the Huntly power station, something that was essential for (literally) keeping the lights on and EVs fuelled when water ran low in New Zealand in the third quarter of this year. These electrons were used by all electricity consumers in New Zealand.

In late 2023 Genesis held an investor day setting out their intention to become net-zero by 2040. Genesis intends to spend $1.1bn on a new renewable investment programme through to 2030, including investing in a solar joint venture, grid scale batteries, and new renewable generation. Genesis plan to displace coal use at Huntly as soon as practical with near net-zero carbon using biomass. Many investment managers support sensible investment decisions to execute this strategy. To fund this Genesis re-based their dividend diverting 100% of the Kupe free cash flow into renewables. The Kupe oil and gas field is expected to be decommissioned in 2036 in line with their net-zero target.

Excluding companies because they emit high levels of carbon today may mean shunning businesses capable of reducing their emissions in the future. The key benefit of being on the transition journey with the high-emitting company is that it promotes engagement with the companies to reduce emissions, rather than ignoring them. Companies like Genesis need to invest to transform their business to net zero. External investment managers can support them in making these strategic decisions.

Although not specific to Genesis (which is 51% government owned), for some heavy polluting companies rather than incentivising these companies to cut back, an exclusion approach may cause them to pollute more. When heavy emitting firms are ‘punished’ by markets with a higher cost of capital, or ultimately starved of capital altogether and pushed towards bankruptcy, they become more focussed on the short-term and may be incentivised to pollute more to generate cash to survive. Bad actors can become worse actors rather than changing for the better. Alternatively, publicly listed companies with higher emissions may resort to private capital and be removed from the stock market altogether, escaping scrutiny from public markets. Owning a portfolio of firms that are already substantially green and can easily get to net-zero does little to improve global emissions.

Image: Lake Tekapo Dam, New Zealand.

We believe investors can make the largest contribution to mitigating climate change by owning, and therefore encouraging, high emitters to decarbonise. Assuming everything goes to plan for Genesis the company’s contribution to global emissions will be materially reduced with offsets likely to take care of the remainder, as it transitions to be a 95% renewable generator by 2035. Investors who have supported the company on this journey should also enjoy the positive returns from a re-rate to a higher, ‘green’ earnings multiple.

Jason Lindsay is Head of Equities at Octagon Asset Management