Analysis: A well-diversified New Zealand bond portfolio should include both corporate and government bonds.

The past couple of years have been challenging for domestic bond investors. The Bloomberg NZ Bond Composite 0+ Yr Index declined approximately 6% in 2021 and 7% in 2022. However, in 2024, declining interest rates led to a strong recovery in bond returns, reaffirming the importance of bonds in a well-diversified portfolio.

According to the September 2024 Morningstar KiwiSaver Survey, nearly 40% of KiwiSaver assets are allocated to cash, New Zealand bonds, and international bonds. Given this, it’s timely to revisit a key concept in bond investing: credit risk. Specifically, we’ll explore the differences between government and corporate bonds, their risks, and returns.

The credit spread

Put simply, when we lend to a non-Government or corporate issuer, we expect some extra return over and above what we would get if we were to buy a bond from the Government. That difference in return is the credit spread.

This is fairly intuitive; the New Zealand Government is unlikely to default on its obligation to repay the interest owed or the face value of the bond at maturity. Global ratings agency S&P Global assigns its highest issuer domestic credit rating of AAA to the New Zealand Government.

Typically, New Zealand corporate bonds, as assessed by recognised credit rating agencies, receive ratings somewhere between BBB- and AA. Lower credit ratings represent ever-increasing likelihoods (compared with government bonds) of the issuer being unable to pay your money back. Why would this be so? Because corporate issuers don’t have the same levers to pull if they run into trouble. Thankfully, defaults on corporate bonds are very rare in New Zealand.

As an issuer’s creditworthiness changes, investors adjust the return they demand, influencing credit spreads, which in turn (all else being equal) affects the price of the bond. Other risks to consider include term premium (compensation for holding bonds over time), default recovery risk (magnitude of potential losses if an issuer defaults), and liquidity risk (the ability to sell a bond before maturity).

How much is enough?

So, how much extra return does an investor actually get in New Zealand for buying corporate bonds rather than government bonds?

To answer this question, we need some data on index returns; we have chosen to use the S&P New Zealand Investment Grade Corporate Bond 1-5 Years Index to represent the average return on New Zealand corporate bonds and the S&P New Zealand Sovereign Bond 1-5 Years Index to represent the average return on New Zealand government bonds.

Both indices have similar durations (sensitivity to changes in interest rates), approximately isolating the impact of credit spreads on returns. We must caution, however, that this analysis will be an approximation, noting that the respective index duration will be a function of the different securities included in the two different indices.

^S&P NZ Investment Grade Corporate Bond 1-5Y Index *S&P NZ Sovereign Bond 1-5Y Index

Table 1 demonstrates that, over 10 and 15 years respectively, you’ve been around 1.5% and 1.8% better off in corporate bonds than in government bonds. Of course, return is only one part of the investment equation – we also need to consider risk, proxied here using standard deviation or volatility, which we define as the movement up and down in the value of each index.

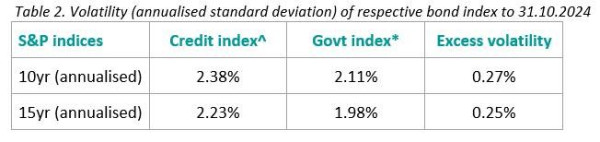

^S&P NZ Investment Grade Corporate Bond 1-5Y Index *S&P NZ Sovereign Bond 1-5Y Index

As expected, by taking some credit risk, you do take on a small amount of extra volatility but, given the quantum of potential excess return is comparably larger, we believe a rational investor would be comfortable with this extra volatility.

Given that corporate bonds appear to provide decent extra returns for just a little extra volatility, why should we even consider having government bonds in our portfolio?

Considering government over corporate issues?

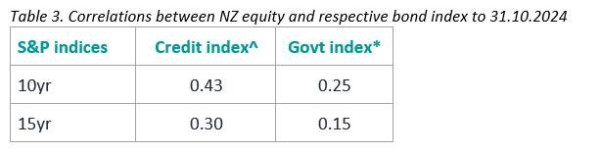

The first reason is diversification: reportedly referred to by Harry Markowitz as the “only free lunch in investing” – the numbers support this too. Look at the correlations between the returns of our two bond indices and the New Zealand equity market (represented in Table 3 by the S&P/NZX50 Gross Index):

^S&P NZ Investment Grade Corporate Bond 1-5Y Index *S&P NZ Sovereign Bond 1-5Y Index

Our analysis over both the 10 and 15-year periods shows that the government bond index has significantly lower correlation to the New Zealand equity market. This is important for investors that also have equities in their portfolios – especially here in New Zealand, where many listed equity issuers are also issuers of bonds.

If the unlikely happens and a New Zealand corporate does default, it could be a double whammy for investors holding both the equity and bonds of the same issuer.

Government bonds in a portfolio: Active positioning and risk management

The second reason to include government bonds in your portfolio is their role in active positioning. If an investor believes that New Zealand’s economic outlook is weak, potentially leading to wider credit spreads and higher yields (resulting in lower prices) for corporate bonds, they may choose to reduce their corporate bond holdings. These can be replaced with higher-rated government bonds, which do not carry credit spreads and would remain relatively unaffected if this hypothesis proves correct.

Additionally, government bonds offer a straightforward way to adjust the duration of your bond portfolio. Due to their high liquidity, New Zealand government bonds are often easier to buy and sell in the secondary market compared with corporate bonds. This makes them an efficient tool for managing interest rate risk.

We believe that a well-diversified New Zealand bond portfolio should include both corporate and government bonds. The additional return from credit exposure balances the lower volatility provided by government bonds. This balance is especially important in a multi-asset portfolio, where government bonds’ lower correlation with equities enhances overall diversification.

Liam Donnelly is the fixed interest and ESG analyst at Octagon Asset Management